Behind the Big House program developers suggest that you consider several things as you move through program development: funding, partnerships, audience(s), goals, and format. Below are suggestions for addressing each of these. These sections are separately categorized, yet are interconnected. For a more detailed discussion on the Arkansas program’s development, see Dr. Jodi Barnes’s presentation (below) from the 2018 Best Practices for Interpreting Slavery in Local Communities workshop in Holly Springs.

This page also includes several challenges that Behind the Big House program developers have faced, and things to consider when approaching these challenges.

Partnerships

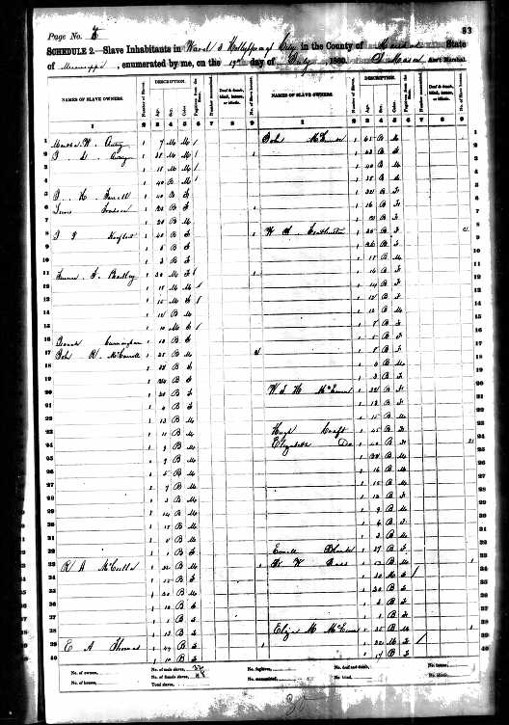

- After you identify a site, partner with someone who knows the history of the site. Look to local historians and archeologists, who may have done history or archeological surveys on the site. Also, check with site owners (public or private) who might have information on former owners, including family genealogical information. Also, look to local historians of African American history and culture. Oral traditions and family genealogies are hugely important in African American communities where ancestors were often unable to record their experiences in writing. The Holly Springs program has had the benefit of working with genealogist Deborah M. Davis. Davis is an Illinois native whose ancestor George was enslaved by Mary Malvina Burton, antebellum owner of Burton Place, one of the Behind the Big House program sites. Thanks to Davis, program developers now know the names of 67 of the 87 persons enslaved by Burton. Those names were added to the 1850 and 1860 slave census schedules and then displayed in one of the slave quarters at Burton Place.

- Partner with organizations which share your goals. The Arkansas program looked to their preservation network for suggestions. This included Jodi Barnes’s colleague, Dr. Jamie Brandon, who suggested they collaborate with Historic Washington State Park in southwest Arkansas. Brandon did archeology at the site and thought the Sanders Kitchen there would be an ideal location. They also wanted to partner with the Black History Commission, since the commission works to raise awareness of the contributions and impacts that black Arkansans made to the state’s history. For the Holly Springs program, Carter and Eggleston began by contacting Joseph McGill, Jr., a friend of Eggleston. As part of his Slave Dwelling Project, McGill agreed to partner with them. McGill knew of no other comparable citywide slavery tours, but agreed to help with interpretations. That first year, they also partnered with the Ida B. Wells-Barnett Museum and the Holly Springs Garden Club, in concert with the Garden Club’s Annual Spring Pilgrimage Tour of Historic Homes and Churches.

- Consider the pros and cons of your partnerships. Some organizations might be doing what seems to be comparable work to the work that you want to do, but do not share the same goals. For example, they could be interpreting colonial or antebellum properties, but not interpreting the lives of enslaved persons at those sites. This does not mean that you should cancel them out automatically. This means that you should determine if they are willing to do such interpretations, and then find out how you can collaborate. If they do not seem interested, then present the potential benefits of doing such work, without pressuring them to participate. They may come around at a later time.

- Keep in mind that some grants require that the applicant organization and humanities scholars collaborate in preparing the grant application. So, line up a crew of humanities scholars to help with on-site interpretations. This means that you should take the grant requirements for a humanities scholar into consideration. Humanities scholars have a range of expertise, including American Studies, Classics Studies, Archeology, Cultural Anthropology, Asian Studies, English, Women’s and Gender Studies, History, Media & Communication Studies, Modern Languages, Philosophy and other liberal arts fields. Granting institutions might require that your humanities scholar teach in one of those disciplines at an accredited institution of higher learning or that they hold a M.A. or Ph.D. degree in such a field. In some cases, individuals will be considered humanities scholars by virtue of special experiences, expertise, or achievements, such as publications in one of the fields of the humanities. For the Behind the Big House programs, Michael Twitty’s expertise in culinary history, Joseph McGill’s expertise in slave dwelling interpretations, and Jerome Bias’s expertise in African American foodways interpretations all fit within the latter category.

- Look to local schools. In 2013, the Holly Springs program began to partner with Holly Springs and Marshall County schools on student site visits. Thanks to Linda Turner, the program’s local school facilitator, between 400-600 students have attended the program each year. These visits generally occur from Thursday-Friday of the program week. In 2012, the Holly Springs program began to partner with Dr. Jodi Skipper, an anthropologist at the University of Mississippi. Skipper heard about the program, through Joseph McGill Jr., and asked Carter and Eggleston to give a tour to teachers participating in a Gilder-Lehrman Institute of American history workshop on “Race and Tourism in the Modern South.” Shortly after, she began to include the program as an applied component in her southern heritage tourism course. Students in that course, as well as those in her African diaspora courses, work as program guides. In 2014, Skipper’s colleague Carolyn Freiwald, a bioarchaeologist, began to partner with the program as part of her biocultural anthropology course. She and Skipper co-managed an archaeological excavation around the Craft House kitchen/quarters to better understand foodways practices in the Craft households.

Funding

- Secure a grant funder if you can. The Mississippi Humanities Council has a regular grant which has been the chief source of economic support for the Holly Springs program. This grant has two deadlines per year. Your state humanities council might offer something comparable. Dr. Jodi Barnes suggests that you 1) not wait until the last minute to review the application, 2) highlight how you are collaborating with other organizations, 3) show how your project is socially relevant, 4) demonstrate the long-term impact of your project, and 5) outline your humanities content. Look to the National Humanities Alliance for more information on humanities subjects and models for humanities-engaged programs. The Mississippi Humanities Council also has a rolling grant, with no set deadline, for those with smaller programming goals. Keep in mind that grants like this might restrict you to programming that is free and open to the public.

- Prior to seeking grant support, you should determine if potential partners might be interested in partnering with you on a grant and sharing program costs.

- There are 49 national heritage areas in 32 states across the country that support a diversity of conservation, recreation, education, and preservation activities. Some of them, like the Mississippi Hills National Heritage area, have community grants programs. Find a National Heritage Area near you to determine if they might offer funding support.

- The Mississippi Development Authority also supported the Holly Springs program’s promotional funds for five years. Your local tourism and recreation office may also be able to offer some economic support.

Audience

When Carter and Eggleston first developed Behind the House, they presented the program as a much needed addition to the Garden Club’s pilgrimage, then a nearly 75 year tradition of home, church, and cemetery tours. Rooted in the historic Natchez, Mississippi Spring pilgrimage tour, the Holly Springs pilgrimage largely centralized the experiences of elite antebellum white families. The Behind the Big House 2012 pilot year was aimed at pilgrimage attendees, trying to expand that base. African American visitors to the program gradually increased, due to better publicity and word of mouth. African American visitors mostly increased after a local citizen Linda Turner visited the program in 2012. In support of the program, Turner arranged to have local Holly Springs and Marshall County students visit the program beginning in 2013. African American students make up a majority of the county enrollment and an overwhelming majority of the city schools enrollment. By 2014, local school groups made up approximately 40% of the program’s total visitation. The program has remained free and open to the public to attract as wide of an audience as possible.

When Dr. Jodi Barnes presented a pilot program to the Preserve Arkansas Board, she knew there was interest in developing new educational programs to reach wider audiences. Preserve Arkansas often charges registration for their events, but program developers thought Behind the Big House should be free in order to reach that wider audience. As a result, they applied for a major grant from the Arkansas Humanities Council. The Humanities Council wanted to know who their audience would be. They proposed that the free two-day program was designed for Preserve Arkansas members, public interpretation specialists, museum curators, historic preservationists, educators, and members of the public interested in the history of Historic Washington, specifically, and African American history more broadly. Unlike the Holly Springs program, they had to consider seating capacity for their attendees. They considered how many people they could practically accommodate, and provided some incentives for attendance, like Arkansas Department of Education professional development credits for attending this workshop. Also, see the University of Mississippi’s Office of Professional Development and Lifelong Learning CEU Eligibility requirements as an example. Something comparable should be offered in your state.

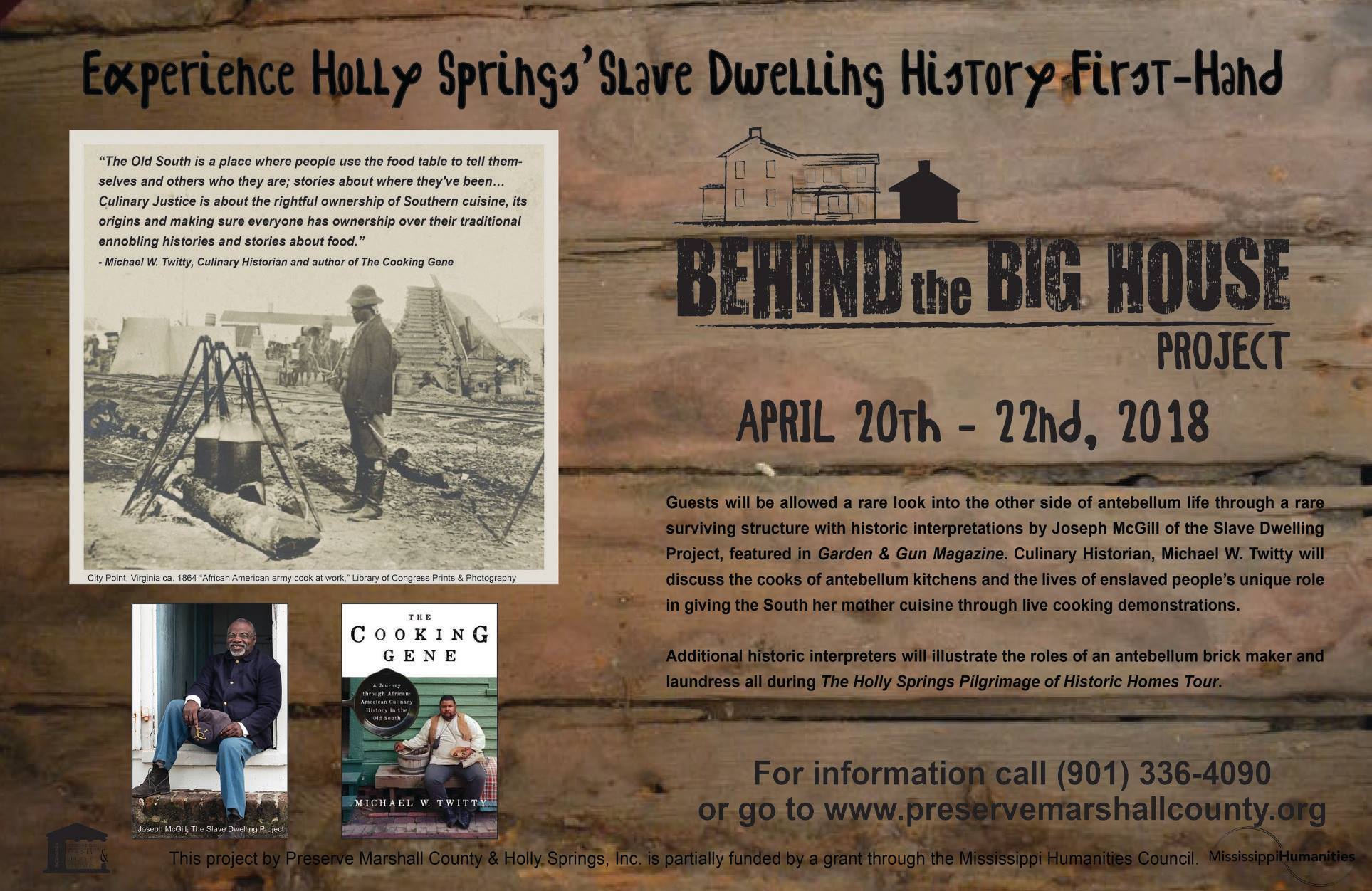

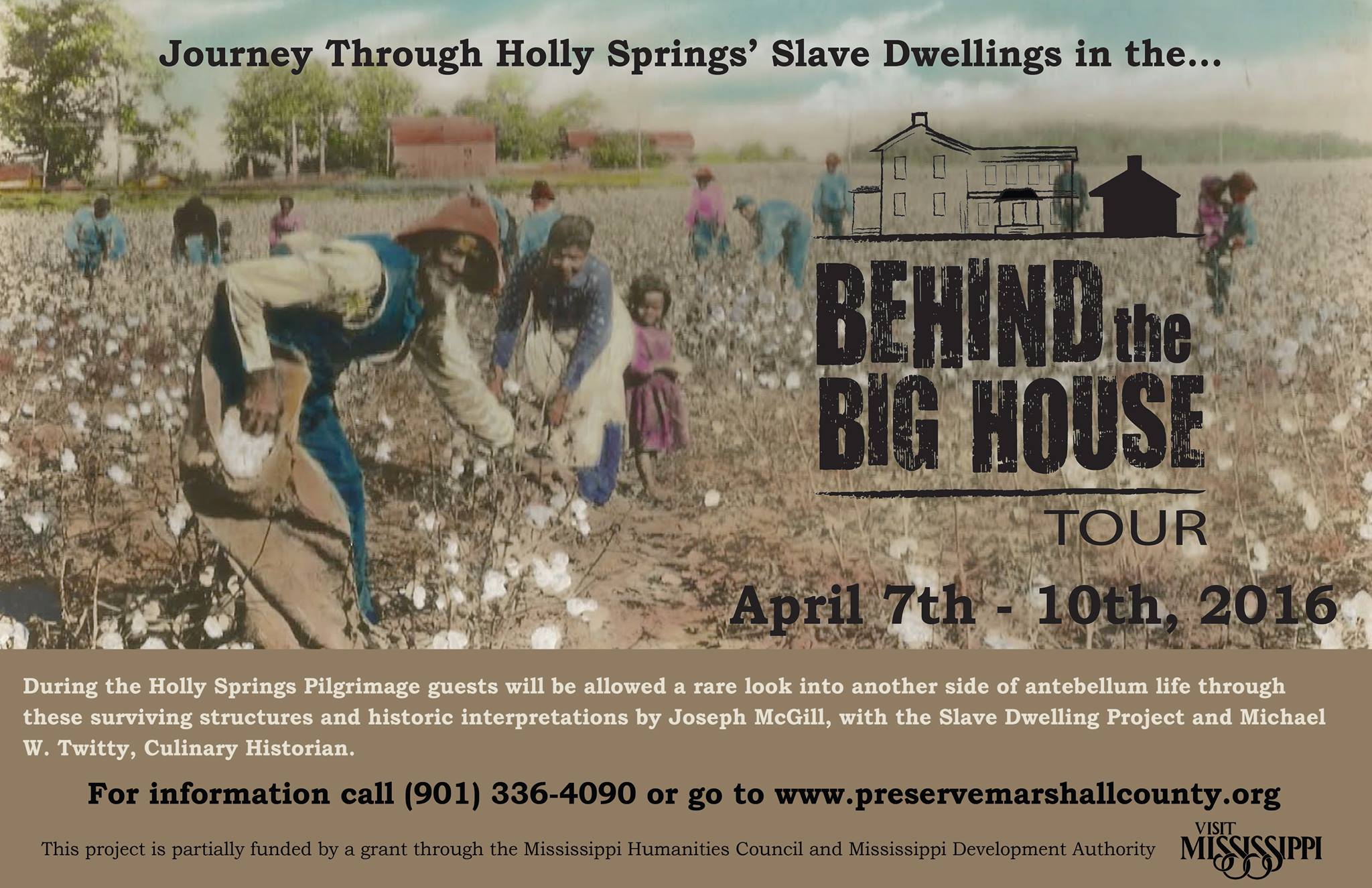

The Arkansas program utilized their networks, such as Preserve Arkansas, the Arkansas Archeological Survey, Arkansas State Parks, and the Black History Commission of Arkansas, to publicize their program. They also publicized the event on a national public radio station, social media, newspapers, and on educator and history listservs. Preserve Marshall County published in several local, statewide, and regional (mid-South) newspapers. They also print event posters, to be displayed at businesses in Holly Springs and in nearby cities. Posters should not only represent the program, but be designed to attract your target audience(s).

Some publicity outlets may be more receptive than others. This might depend on their target audience. Look for publicity outlets that attract the audience(s) you hope to attract. Other publicity outlets may take some time to get on board. After several attempts at coverage through Mississippi Public Broadcasting, the Holly Springs program was featured in April of 2018, thanks to reporter Ashley Norwood. Support from an interested reporter, like Norwood, can be helpful.

All forms of publicity should be considered when determining program costs.

Goals

Dr. Jodi Barnes suggests that you 1) set goals and then 2) think about what kind of program will help you reach your goals. You should keep in mind that goals should change as programming needs and partners shift.

The Holly Springs program’s initial goal was to present a much needed alternative to the Garden Club’s pilgrimage narrative, one which omitted complicated narratives of slavery. Since 2012, their programming goals have become independent of the Garden Club’s. Local youth and community education are its primary goals, with the intent of modeling the program as a portable template for any historic site, community or region who recognize the need to re-tool their own historic narrative and have the political will to do so. This website is critical to that goal.

The goals for the Arkansas program have changed each year. To Dr. Jodi Barnes, the model is not a cookie cutter model that can be picked up and taken to a different location. They are constantly thinking about how to make it better and checking out what others are doing to get new ideas. They struggle with how to keep the program from being a top down program with a one sided sharing of information, with professionals providing information to the audience. In the upcoming years, they intend to include more panels and other formats to create more dialogue, and think about ways to provide more useful tools for people to do their own research or develop their own programs.

It is very helpful to consider reciprocity as a programming goal so that you are not only bringing community partners into a program, but assisting them with their individual or institutional goals. One of Dr. Jodi Skipper’s greatest achievements was the ability to pay some community partners for their contributions to her workshop in Holly Springs, through a Whiting Foundation Public Engagement Fellowship. As part of her fellowship goal, Skipper organized a Best Practices for Interpreting Slavery in Local Communities workshop. Skipper received the fellowship as a result of her work with the Behind the Big House program, and was then able to reciprocate by compensating some community partners for their help with the workshop. To Skipper, this is reciprocity at its best.

The Holly Springs program largely depends on the kindness of several private homeowners, whose historic properties have historic preservation needs, specifically daunting rehab projects. Local Holly Springs community and youth education is still the Holly Springs program’s main goal, yet Carter and Eggleston noticed a fair amount of interest in surveying and preserving historic structures. Behind the Big House program developers and partners hope to prioritize this as a program goal.

Program Format

Research

When Carter and Eggleston decided to start their own tour, they selected two sites for interpretation; one on the Garden Club’s pilgrimage and one not. This would not only guarantee that pilgrimage participants be exposed to the slave dwelling interpretation program, but that there would be another slave dwelling site for comparison. This program would be tour-based with a separate interpretation experience at each site.

Before determining the format, Holly Springs program developers did a reconnaissance survey of extant resources, for mapping. These resources were later presented on a program brochure.

Carter and Eggleston also searched for primary historical resources, including slave-owning family narratives, like Craft/Fort Family Letters at the University of Mississippi Department of Archives and Special Collections and the Marshall County Historical Museum. They also looked at census data, like 1850 and 1860 slave census schedules,

Marshall County WPA slave narratives, and historic images, like this mid-nineteenth century daguerreotype of the Craft Family, with what seems to be a well-dressed black man to their right, on the front gallery of their home. The slave dwelling, also the kitchen, is in the background.

This photo is courtesy of the Chesley Thorne Smith collection. Smith grew up in the Hugh Craft house.

Keep in mind that WPA narratives are largely the narratives of people enslaved as children, many no longer living in the counties in which they were enslaved, when interviewed. This means that if you are looking for the experiences of those enslaved in a particular county, then a much wider records search might be needed. Secondary sources on the antebellum histories of a particular state, and related counties, can also be helpful for a general historical context. These sources, especially older ones, are likely to neglect the experiences of enslaved persons. Finding voices for the historically silenced is a challenge, but not impossible. The oral histories and historical memories of African American descendants can be invaluable, as well as the assistance of contemporary historians of colonial and antebellum histories.

Carter and Eggleston used the sources they were able to locate to develop a general narrative for interpretation. Your narrative should shift as information is revised and added. At Burton Place, one of the Holly Springs slave dwelling sites, the interpretive narrative changed after Deborah Davis, a descendant of those enslaved by the antebellum owner of the site, contributed much needed genealogical information.

The Tour

The Holly Springs program generally begins with an opening reception, with introductory talks from participants like Joseph McGill, Jr. and Michael Twitty. The reception is open to the public, yet requires a reservation so that food preparations can be made.

Although not on tour, the Hugh Craft main house is the headquarters for the Behind the Big House program. One to two weekdays are generally reserved for school group visits. At the Craft House, each school group is given an orientation on slavery in Marshall County and then proceed to home sites, generally each within two blocks of each other. Other tourists are given program maps and brochures, and general information on the tour. Each quarters’ site includes slave census schedules and a visualization of the antebellum property, sketched by Chelius Carter.

Each site has guides who interpret the spaces occupied by enslaved persons, and answer visitor questions. These volunteers range from local community persons like Rkhty Jones; to Dale DeBerry and Wayne Jones, who give brickmaking demonstrations; to site homeowners like David Person; to University of Mississippi students in Dr. Jodi Skipper’s southern studies and anthropology courses.

Joseph McGill, Jenifer Eggleston’s former colleague and friend, began giving Behind the Big House program tours in 2012 and has continued to do so. McGill, founder of the Slave Dwelling Project, offers a more general narrative about the experiences of enslaved persons, less specific to each site. In addition, from 2015 to 2018 afro-culinary historian and chef Michael Twitty demonstrated food preparation practices, in the yard space between the main house and detached kitchen at the Craft House. Twitty alternates between food prep at an outdoor cooking fire and narrating the detached kitchen, which would have housed an enslaved cook.

The Holly Springs tour has ranged from interpretations of seven homes, to three homes, to one, with a more rounded experience at the one site. A tour of three homes, in close proximity to each other, has been the most typical experience. It is more manageable than seven homes, and gives more diverse representations of slave dwelling sites than one home. You should determine what is practical for your program, if you choose to span the program across sites.

The Arkansas program format has varied. It focuses on one site per year. See Dr. Jodi’s Barnes’s presentation for a more complete explanation.